Historicising Media Arts

The Role of Documentation and Records of Festivals

Bilyana Palankasova (Glasgow) and Sarah Cook (Dundee)

A recent email exchange between curator Sarah Cook and art historian Gabriella Giannachi concerning a published account of a restaging of the artwork Hole in Space (1980) by Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitch noted the differences in descriptions of the artwork from one showing at a festival exhibition to another showing in a museum, prior to discussions about the work potentially entering that museum’s collection. The festival was AV in Newcastle in March 2008, and the artwork was part of the exhibition Broadcast Yourself co-curated by Sarah Cook and Kathy Rae Huffman. The museum display was at SFMOMA in November 2008 as part of the exhibition The Art of Participation curated by Rudolf Frieling. The differences pertained to how audiences encountered the work – re-presented from video documentation of an original live event – and whether there was a ‘new’ or ‘first-time’ experience in the museum’s re-presentation (as described in Giannachi 2022: 140–141), or whether in fact the AV Festival re-presentation had been the ‘first’ time that the work had been restaged in that way. The exchange revealed that records documenting the re-presentation held by one team of curators (Cook and Rae Huffman) hadn’t been accessed by another team of curators (led by Frieling) because they weren’t aware of those records, either because the artist hadn’t mentioned it due to timing or they hadn’t had opportunity to fully research earlier re-presentations of the work (despite some public records being available online documenting the work in the AV festival’s exhibition). This anecdote neatly illustrates concerns around the different timescales of producing exhibitions at festivals or museums, including research, production, or documentation and how the types of documents and their accessibility affect institutional memory.

In this text, I’ll consider the documentation of festivals of media arts and the relationship between an expanded sense of documentation and the writing of art histories against traditional institutional contexts and discourses. This article emerged from my doctoral research, and a version of these ideas was first presented with Sarah Cook at Transformation Digital Art 2023: International Symposium on the preservation of digital art hosted by LIMA in Amsterdam in February 2023.

Firstly, the essay starts by drawing the context in which festivals of media arts are considered historically, their activities, and how they relationship to media arts informs their position in relation to institutional discourses. Secondly, the text maps out the kinds of records of festivals that exist, considering private and public and internal and external documents which serve as artefacts of exhibitions and programmes. Thirdly, it considers how we might value and historicise media arts prior to their entry into institutional space.

How do we think of festivals?

(New) media art[1] has often been described as sitting “outside the traditional boundaries of art world validation, making its own exhibition contexts” [Diamond 2003: 154] and it has been argued that digital art made its debut in the mainstream art world in the late 1990s with its inclusion in the programmes and exhibitions of museums and galleries [Paul (2003) 2015: 23; Gere 2008: 21]. This period coincides with the emergence of net.art in the mid-1990s and the discussion about art and technology on mailing lists and websites like Rhizome, Nettime, the Whitney Museum’s artport, and CRUMB [Gere 2008: 22]. In the UK in 1997, The Small Grants for New Media scheme was established to focus on small-scale experimental projects in distributable electronic media formats, which signalled institutional shifts in the perception of art using digital technologies [Allthorpe-Guyton and Cadwallader 2004: 7].

This is not to say that there had not been digital art activity prior to that. There had been a vibrant digital art scene outside of traditional and mainstream contemporary art spaces and digital art shows were presented in institutional contexts at media centres and museums such as the Intercommunication Center (ICC) in Tokyo or the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe. During the previous two decades, the main spaces that showcased digital art were Ars Electronica festival (Linz, Austria), ISEA (International Symposium on Electronic Art), EMAF (European Media Arts Festival, Osnabrück, Germany), DEAF (Dutch Electronic Arts Festival, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), Next 5 Minutes festival (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), transmediale festival (Berlin, Germany), VIPER (Lucerne and Basel, Switzerland) [Paul (2003) 2015: 23]. This festival-rich list could also be expanded with the inclusion of Lovebytes festival [Gere 2008: 21], Node.London, AND (Abandon Normal Devices) and AV Festival [Cook 2012]; Media City Seoul (now Seoul Media City Biennale) and Festival Montréal du Nouveau Cinema et Nouveau Media [Diamond 2003: 142].

Festivals are of interest since the scholarship on media arts documentation is often concerned with the practices of museums or other collecting large-scale institutions [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 200–202]. Festivals are non-collecting, transitory, ephemeral cultural forms and conceptions about value and festivals are informed by their perception in scholarship as hybrid and networked cultural phenomena [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 222]. Despite the suggested importance of festivals in the production and platforming of media arts historically, a thorough account and historicisation of their activities and significance is still lacking. At the same time, the relationship between media arts and traditional institutions has been widely discussed, however, mostly in terms of media arts presence in institutional exhibitions and collections as evidenced by the historical emphasis of media arts entering the museum during the 1990s outlined above. Artistic discourse and art history tend to be written from the perspective of the institution and as such, artistic and cultural processes taking place outside and alongside such established structures often remain unaccounted for. This text suggests that an expanded sense of documentation, which includes record-keeping and creation beyond the traditional documentation of exhibitions or events by the presenting institutions or participating artists, could inform the writing of art history.

The reluctance of mainstream art institutions to respond to new practices involving digital technology through the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century has been viewed as a provocation for the appearance of alternative platforms for presentation, distribution and contextualisation of emergent practices and the distinct histories of these practices are often related to festivals [Krysa 2006: 18]. Festivals have a strategic importance in the presentation of emergent art practices because of their key role in shaping new forms of creativity, particularly in the development of art involving electronic and digital technology, by “recognising, conceptualising and defining dominant artistic practices in the process of their development” [Krajewski 2006: 223]. Festivals are seen of particular importance since they represent an alternative (often countercultural) narrative and character in relation to established traditional art institutions [Krajewki 2006: 225]. And importantly, festivals have formats well suited for demonstrating work in progress, emphasising process and inviting feedback [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 218]. In Sara Diamond’s words “An emergent practice requires a nimble response from institutions. Museums and galleries may need to be more like laboratories, with outcomes that show work in progress” [2003: 156].

While a short-lived festival format reflects the unstable and temporal characteristics of new media, festivals have been perceived as focusing on “delivery” instead of “critical debate or producing knowledge around certain practices”, but as Cook suggests, there are exceptions to this [Cook and Barkley 2016: 508]. For example, Ars Electronica included workshops and symposia, that are crucial in facilitating context for critical debates and thus actively contributing to the development of critical discourse around new artistic practices [Krajewski 2006: 227]. Later in this text, a few other examples are presented further evidencing the generation of discourse through festival programmes. Similarly, festival programmes have been characterised as reflecting tension between the time to explore and conceptualise and the time to produce and deliver, especially in terms of planning and production timelines compared to larger institutions like museums. If festivals can strike a balance between these pressures, they can fill unique niches where new ideas and artistic experiments “are incubated successfully” [Mitchell, Inouye and Blumental 2003: 128]. In reality, the suggested tension could be mediated through an emphasis on collaboration, co-authorship, and audience engagement, particularly by working on making ideas at the core of an artwork accessible to audiences by allowing a “workshopping” of ideas similarly to creative processes in an artist’s studio [Cook 2016: 391]. Such fundamentally discursive curatorial methods facilitate knowledge generation around practices and evidence the emergence of discourse at festivals of media art. However, these process-based and live forms (workshops, symposia) come with their own challenges and resistance to documentation, while they are also of key importance to the organisational memory and cultural legacy of festivals. These understandings of media art or digital art festivals emerge at the same time when “new media art” is the predominant terminology for artistic practices using new digital technologies and describing a distinct phase in the history of digital arts.

(New) media art and institutions

Significant amount of discourse around digital art emerged shortly after the turn of the 20th century and is specifically rooted in “new media art” as a defined field of art made with digital technology, which has distinct characteristics. Notably process-oriented, new media is inherently collaborative, participatory, networked and variable [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 8] and tends to challenge the structures and logic of museums and art galleries and reorients the concept and arena of the exhibition [Cook and Barkley 2016: 498]. In this context, new media art seems to call for a “ubiquitous museum” or “museum without walls” [Dietz et al. 2004, cited in Cook and Barkley 2016: 501] – a parallel and distributed information space open to artistic interference – a space for exchange, collaborative creation, and presentation that is transparent and flexible [Paul 2006: 1]. In this tradition, new media art has also been described as requiring hybrid institutions that operate more like systems than spaces for art – such hybrid platforms are valuable because they allow for audience engagement flexibility and foster interdisciplinary projects, blurring the boundaries between art, interaction, and learning, while emphasising sill sharing [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 222].

The curator and media art historian Christiane Paul elaborates that new media is logically opposed to traditional institutional forms and structures and is, by its nature, a form of institutional critique through its challenging of the traditional boundaries of the museum and its roots in multiple contexts, some of which outside of that institutional space (2006). In this context, institutional critique as related to (new) media art, is not meant as the art-historically defined field of artistic practice but rather is aligned with the institutionalisation of Institutional Critique and what followed in the form of New Institutionalism[2]. The curator and critic Jonas Ekeberg defined New Institutionalism as “an attempt to redefine the contemporary art institution […] ready to let go, not only of the limited discourse of the work of art as a mere object, but also of the whole institutional framework that went with it” [2003, as cited in Möntmann 2009: 155]. While this description is aligned with larger processes at the time having to do with the emergence of curatorial practice as a distinct knowledge-producing practice, it also echoes the relationship between media art and institutional structures in the artworld. In her discussion of new media art and Institutional Critique, Paul roots her argument in the art form’s inherent qualities, especially its immateriality, collaborative creation and wider characteristics of digital networks and claims that through its diverse forms, new media art intersects with Institutional Critique where it questions “the status and the role of the art objects as well as institutional processes” [Paul 2006: 1–2].

In an adjacent concern, the media theorist Ned Rossiter speaks of organised networks as an alternative to contemporary institutions by “reconciling their hierarchical structures of organisation with the flexible, partially decentralised and transnational flows of culture, finance and labour,” stressing that the advantage of organised networks is their functioning as socio-technical forms emerging from digital technologies [2006: 14–15]. In this theoretical tradition, the art theorist Nina Möntmann conceives of the new institution in the art world as an information pool, a hub for transdisciplinary collaboration, a union and an entry for audiences to local and international participation and exchange [Möntmann 2009: 159]. These institutional imaginaries are strongly influenced by the rapid developments in digital technologies at the time and the perceived possibilities for challenging the cultural status quo that they bring.

There seems to be logical proximity between the characteristics of such imagined new networked and open institutions in discourse from the first decade of the 20th century and the aesthetics and behaviours of media arts. At the same time, the abundance of media art festivals as facilitating cultural networks and delivering experimental and process-oriented programmes, is historically aligned with the same theoretical and practical developments relating to the institutional spaces of contemporary art. In this framework, festivals could be positioned as networked, collaborative, and transdisciplinary organisations which at the time played a particularly important role in creating spaces for the presentation and development of emergent practices which were not readily embraced by institutional structures. In this context, it is useful to draw on Paul’s perspective of the institution as a node in a larger artistic and cultural systems, supporting the existence of the artwork through other nodes – Paul asks whether new media art has caused a “departure from institutional critique towards a form of ‘transgressive ecology’ as an environment of shared resources that allows for divergence, fluctuation, and interpretation between localities and bodies of knowledge” [Eduardo Navas 2005, cited in Paul 2006: 10]. While the realisation of this transgressive ecology, as described by Paul, is perhaps still to be achieved, the concept is nevertheless useful and aspirational to position festivals against, and in thinking beyond traditional institutional contexts.

With this in mind, how could we consider expanded documentation in the context of such transgressive ecology, where documents of a particular work could exist in multiple social domains with varying level of visibility or access? When thinking of documentation for the purposes of research and historiography, where do we look for documents and records of artistic practice beyond the formal documentation by traditional institutions where certain practices or works might have not yet been introduced? The writing I draw on here is reflective of a particular period in time, mostly the first decade of the 21st century, therefore this is a proposition to chart the documentary presence of artworks and curatorial projects in that period.

A major event marking this period and impacting cultural change is also the global financial crisis of 2008. In more recent scholarship, the artist and theorist Bill Balaskas positions crises as catalysts for institutional transformation and “commons” as key in enduring periods of crisis. He positions the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 as a context and catalyst for institutional transformations and considers the epistemic conditions of networked media and collaboration as having a transformative impact on art institutions [Balaskas 2020: 181). From this, an alternative reading of “commons” emerges in this post-crisis environment – instead of being conceptualised in the traditional way as natural resources, cultural and intellectual production, infrastructure, education etc., “commons” has radically expanded during the last decade to now describe “everything that we are in a position to jointly research, create, and share – particularly through the production and dissemination tools offered by networked technologies” [Balaskas 2020: 181–182].

This is of particular importance, since it suggests a larger cultural and institutional shift related to digital technologies which took place alongside the intense development of (new) media art. It is key that digital technologies have had a profound impact on the ways in which art is distributed and reproduced. The development and prominence of collaborative and research curatorial activity alongside art and digital culture is of importance and also echoes Paul’s proposition of the institution as a node, suggesting collaborative work with other organisations and individuals in the same artistic ecosystem expands the scope, criticality, and audience of networked institutions.

My proposition in this context is that media art festivals have been prototypes for such networked and open institutions while at the same time their historicisation has been impeded by the resistance to documentation of a lot of their curatorial approaches (which prioritised experimentation, emergence, and process in art practice). In this sense, we need methods to document and historicise the festival qualities and conditions of experimentation, emergence, and process that they are associated with.

Where do we find festival records?

Cultural value tends to be placed where institutional or curatorial authority is – often expressed through the formal museum or gallery documentation. But [traditional] institutions also bring a sense of history and security to the table, particularly through their critical role in the creation of archives and databases of new media work [Diamond 2003: 160]. “Historically, museums have been defined by their collections and the role of the curator has been defined by a registrarial duty” [Cook 2003: 170]. At the same time, non-collecting institutions also document their past exhibitions by filling “publicity materials, catalogues, press clippings, educational event documentation, installation shots, correspondence, and items without a taxonomical home to go to” [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 200]. In the context of media arts specifically, another complication arises from “the whole question of what to document and archive” being accelerated by new media [Thompson 2002, cited in Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 200]. In this context, it is useful to think about where documents of non-collecting organisations might sit outside of the boundaries of the organisations themselves.

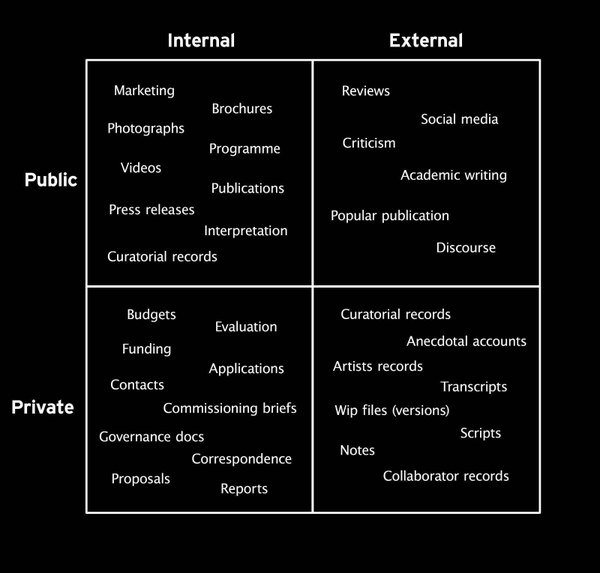

The documents and records of festivals (or any cultural organisation) exist on two axes – private/public and internal/external (Fig. 1). Private and public refer to the availability of records to the public. Internal and external refer to the origin of the document – whether that’s the producing organisation or external collaborators, scholars, press etc. By classifying document types through this matrix, documentation is approached in an expanded sense, not strictly considering the formal documentation of projects produced by traditional cultural institutions (museums for example) but including various kinds of records which might exist about a work of art, an exhibition, or a programme.

Fig 1. Where records of artistic activity are distributed through the cultural network.

Internal (Public & Private)

The public-facing category is occupied by records such as photographs, press releases, brochures, programmes, and publications – this ephemera produced around a project is the public memory of the organisation and is an image performed by the organisation for an audience.

The private organisational documentation relates to funding, grants, contracts, evaluation, which reveal significant information about projects, festival editions and how artworks come to be. These are private records which scholars or cultural workers might be able to access by consulting an organisation’s records or archives. They are a key part in the memory of the organisation and could be instrumental in writing its history and conceiving of its archive.

External (Public & Private)

An artwork, a project, or a programme’s overall cultural and social value and capital is closely linked to their visibility and presence in the broader cultural context that they sit in. These records could take the form of popular publications, social media, criticism, academic writing, and discourse more broadly through discursive events like talks, symposiums, or conferences. These represent different channels for value and different models of cultural validation – whether via scholarly interest or via aesthetic appeal to the work throughout social media. Crucially, these kinds of records document the reception and experience of the work in more generative ways that evaluation reports for example.

Private records, which sit out with the organisation could include work in progress files, or versions, scripts, storyboards, notes, correspondence, anecdotal accounts, the artist’s records, and sometimes curatorial records as often festivals do not work with a festival curator but change curators between editions and these are often associate or adjunct curators. Through encounters with different kinds of records, a history, or a toolbox of how organisations generate value could be constructed in order to expand on new ways to activate, produce and perform an organisational archive which is value-led.

While the matrix used helps to distinguish between the types of records based on their accessibility and broad position in various parts of cultural communication, it is nevertheless constructed from the perspective of the organising and producing structure of the phenomena documented. As such the boundaries between the different segments could be porous and some records could be found in various or multiple segments depending on the nature of a project, the country where the activity takes place or the ethos of the organisation. Therefore, such graph in a specific context, could be indicative of both overlaps and gaps in existing records.

In relation to media arts festivals, when looking at organisational records, there are gaps in the external records and often in the accessibility of the internal documentation. What is missing from organisational records which might carry value and be worth preserving as a document of an artwork, exhibition, or programme, particularly in the context of festival programmes with focus on emergent and experimental practices with digital technology? And specifically with reference to the External and Public area, how is engagement with and critical record creation of exhibitions and programmes related to the generation of discourse at festivals and their eventual historicisation?

The documentation of festivals

If festivals are valued for their experimental nature, the absence in the typical documentation approaches and repositories is one which points to the need for festival documentation to capture the experimental nature or the process of emergence of artworks. This knowledge or value will largely sit in the External area of documents both privately in the form of records of participants and collaborators but also publicly in the form of impressions of participants on the Internet for example. This begs questions about the strategies and approaches to recording unstable or experimental processes and particularly whether this documentation is the responsibility of the practitioner, organisation, curator, or somebody else?

The role of documentation of festivals is of interest here since the invisibility of festivals in the historical records and discourse around digital art could be attributed to their poor documentation by way of engaging more with production and distribution (process), as opposed to questions of display or collection (de facto reception) that traditional institutions engage with [Graham and Cook (2010) 2015: 216]. Or in other words, what earlier was outlined as the tension between conceptualising and producing. In a scholarly landscape which is largely preoccupied with the relationship of media arts to the museum, the entry of media arts to collections, and the documentation of media arts for preservation purposes, it is imperative to think about the lives of media artworks prior to their introduction to institutional spaces, and particularly in the context of festivals and adjacent contexts which tend to show experiments or emerging practices. And to consider how the artistic or cultural value of such practices transforms throughout their lifespan and alongside their trajectory from experiments to valued artistic objects in collections.

While sufficient documentation could be dependent on resources, attributing the lack of documentation to the restrictive budgets of festivals reveals only one side of the challenge. For example, there was no lack of documentation of the work described at the start of this article – there were photographs shared on Flickr, news reports, and exhibition reviews in the art press, as well as email exchanges between curators and artists. But there was lack of immediate access to it, and therefore consultation of it, possibly due to the tight timescale between the close of the festival and the start of the exhibition later that same year.

Other than resources, the difficulty in record-keeping in the case of media art festivals also has to do with different curatorial and programming methodologies which might exist at a festival, which are dissimilar to museums’ approaches. For example, good practices in documenting an artwork’s conditions of emergence and display are a symptom of collecting institutions (via iteration reports or similar) and relate to the idea of versions of works, which in itself suggest a process of maturing or gaining value through time. The methodologies of curation of small-scale festival-delivering organisations differ greatly from those of collecting legacy institutions – what earlier in this text was described as difference between emphasis on collection and reception and emphasis on production or delivery; or tension between conceptualising and delivering. How can we reconcile this to establish a trajectory from emergence to collecting of a work as an act of tracing a its path to institutionalisation?

Transience and discourse

Festivals’ transitory format reflects the unstable and temporal characteristics of (new) media art, but also limits their opportunity to engage with discourses – they focus on “delivery” instead of “critical debate or producing knowledge around certain practices” although there are exceptions to this [Cook and Barkley 2016: 507–508]. Two things about this could be unpacked: the relationship between “unstable media” and “transitory festival” (1) and the relationship between “delivery” and “knowledge production” in the context of festivals (2).

- Unstable media & transitory festival: the somewhat unfixed or ephemeral nature of both festivals and media art certainly contribute to a synergy between the two (as is the case with other lively practices, like performance for example). This transitoriness could also be attributed to some festivals’ nomadic nature. However, this transitory form does not limit the opportunities to engage with discourse. I’d argue this is dependent on the particular orientation of individual festivals’ programmes but overall, festivals of art and digital culture are strongly involved with critical debate and produce meaningful contribution to the discourse on digital culture and artistic practice through the inclusion of conferences, symposia and lectures. Through these programming methods and by their themes and nature, festivals are some of the biggest forums for critical debates relating to technology and society and as such have a distinct role in the histories of media arts and their associated discourses.

- Delivery & knowledge production: the implication of delivery as opposed to knowledge production here has to do with the fast-paced delivery, often hasty preparation of a festival, which doesn’t have the same pace as other forms of presenting art, which allow for closer work between artists and organisers or long-term project with thoughtful consideration of various elements. However, in the context of digital art festivals, what the existing scholarship shows, is that they are regarded as and valued for platforming process, experiments, and emerging practices. The knowledge production then happens in the space of these process-oriented and experimental moments at festivals (in the form of workshops or labs for example) which comes with the challenge of documenting these qualities of emergence.

In fact, festivals do produce critical debates and knowledge around practices, their programmes include symposia and conferences which engage in depth with current discourses. transmediale is particularly invested in critical discussions and their programme is up on YouTube alongside a public version of their archive online, ISEA’s proceedings are available on their website. Very early on, Ars Electronica included workshops and symposia, that were crucial in facilitating context for critical debates and actively contributed to the development of critical discourse around new artistic practices. The active documentation of such programmes and tangible contribution to discourse could be useful in reconciling the tension between conceptualisation and production at festivals.

These are all examples of established institutions, but smaller or less mature festivals have also engaged in publishing activity to document their work and discourse emerging around it. For example, the special issue of Media-N Re@act which serves as proceedings from the Re@ct Symposium at NEoN 2019, consisting of essays, artist’s statements and experimental projects; FutureEverthing’s Manual published in 2011 which includes essays, writing around the festival theme alongside the articulation of methods for curating innovation projects; the NODE.London readers project a critical context around the Season of Media Arts in London in March 2006 and 2008; Autopsy of an Island Currency was published by Pixelache in 2014 as a book documenting and reflecting on the process of a 2.5-year project to create experimental currency for the island of Suomenlinna near Helsinki.

The challenge doesn’t seem to be lack of documentation of discourse around these practices by the organisations themselves – the examples above illustrate how festivals have used publishing as a method of documenting their activities, elaborating on their context, meaning and value and positioning them in critical contexts. Rather, the gap seems to be in the external records available or in the records documenting the experience or reception of artworks or projects, for example in criticism or review or the representation of an artwork’s development and trajectory by artists themselves. This discrepancy signals the tension in methods and thresholds of valuation which determine the rhythm, pace, and route of distribution of artworks and draws the lines of entry and inclusion into institutional space. In the case of festivals of media art as distinct spaces for the presentation of art forms historically separated from more mainstream (or institutionalised) practices, these organisations themselves are often in emergence and not part of established circuits nor valued like established institutions.

How does value change over time?

The assumption of this text is that the value of festivals sits with conditions of emergence, experimentation, and process in relation to artworks, or practices. And this is supported by the often open, networked, collaborative and transdisciplinary nature of the work festivals do.

The curator and critic Domenico Quaranta calls the (new) media art world a “temporary holding centre” explaining that once a work is past its experimental stage, it makes its way in other circuits or abandons the definition of “art” in favour of other more specific definitions” [Quaranta 2013: 103]. I would disagree and suggest that it doesn’t abandon but embraces the definition of art and sits with it as comfortably as with definitions like science, activism, or civic practice in a way not dissimilar to contemporary art, despite Quaranta’s claim that (new) media art world hosts all outliers until they mature. The inclusivity of contemporary art in bestowing the status of art to work from different disciplines [Quaranta 2013: 103], which Quaranta refers to has to do with the emergence and increased importance of curatorial practice and expanded projects which position artworks alongside other disciplines and social activities to extend a thesis or a proposition. In itself, this increased emphasis on collaborative curatorial projects focused on “knowledge creation” between disciplines relates to the processes of networked culture discussed in the first part of this text. Rather, this transient perception of the media art world signals emergence and reinforces the importance of documenting such practice prior to their inclusion in museum exhibitions or collections.

The unflattering definition of “temporary holding centre” is from a decade ago and what has changed in that time is the visibility of the process of institutionalisation of media arts. While some legacy institutions in the field have a longer history (ZKM, transmediale, Ars Electronica), the last decade shows the processes of transformation and maturing of existing festivals, alongside the emergence of new ones. The gaps in documentation at festivals (or other experimental small-scale platforms for that matter) are symptoms of the process of institutionalisation of media arts, not of their incapacity to document – while such organisations might document their practices, they haven’t always been perceived as ‘critical’ for example in order to enter the institutional space of art (as a system of values, aesthetics and discourses shaped by large contemporary art institutions).

What Quaranta calls a “temporary holding centre” is the extra institutional space, in which a lot of experimental practices (particularly those using emerging technology) find themselves into. In this sense, writing the history of institutionalisation of media arts (particularly evident in the last decade) is dependent on the scholarly capacity to uncover documentation of festivals which evidences both practices and institutions in emergence.

If media art festivals represent an experimental ground for creative practice, how do we historicise festivals as themselves forms in emergence which undergo processes of institutionalisation? We need to reconcile or close the gap between organisational memory and institutional legacy by capturing the value emerging in the pre-institutional phase of media art practices. Or in other words, festivals while having organisational memory (their records) go through a process of institutionalisation (they become more mature and turn into institutions with time) which comes with establishing their own thresholds of valuation. And through this process they perform their ‘institutional legacy’ by the historicisation of their value and influence.

These processes of value emergence and validation (particularly with reference to media arts) are closely related to concepts of “the new” and innovation as even the insistence of “new media” shows. The invisibility of prototypical or experimental works in these processes and the focus on maturity of works needs to be challenged. Instead, a reading of innovation in which we don’t reaffirm or reject the new but relate to it in new ways might be more productive in articulating developing systems of value and threshold for inclusion into institutional spaces. In this context, it is helpful to think of innovation as the re-valuation of values: “Innovation does not consist in the emergence of something previously hidden, but in the fact that the value of something always already seen and known is re-valued” [Groys 2014: 21]. In this sense, how do we trace the revaluation of artworks through documentation and organisational records and how do we relate to previous iterations in new ways which reveal thresholds of validation or establish mechanisms of valuation? Or if festivals present experimental practices, what documentation do we need to trace the trajectories of these experimental ideas and works through artworld(s) and discourses, which is to trace a process of institutionalisation or entry into institutional space?

[1] In this text, I use “(new) media art” as a way to speak from a contemporary position, in which I use the term “media arts”, while also bridging this with the sources I draw on from the late 1990s and early 2000s, in which “new media art” is the predominant terminology, since it specifically described that period in the history of digital art. Therefore, the term “new media art” will still be present in this text, when discussed in the context of existing scholarship.

[2] A term describing curatorial, administrative, and educational practices and shifts which took place from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s and aimed at reorganising the structure of publicly funded contemporary art institutions and to conceive of and theorise of alternative forms of institutional activity.

References

Allthorpe-Guyton and Helen Cadwallader. “0.1 Preface.” In: New Media Art: Practice and Context in the UK 1994–2004, edited by Lucy Kimbell. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications 2004: 6–8.

Balaskas, Bill. “Networked Media and the Rise of Alternative Institutions: Art and Collaboration after 2008.” In: Institution as Praxis: New Curatorial Directions for Collaborative Research, edited by Carolina Rito and Bill Balaskas.. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2020, 180–196.

Cook, Sarah. “Stop, Drop and Roll With It: Curating Participatory Media Art.” In: Practicable: From Participation to Interaction in Contemporary Art, edited by Samuel Bianchini, Erik Verhagen, Nathalie Delbard and Larisa Dryansky. Cambridge: The MIT Press 2016, 377–395.

Cook, Sarah. “Towards a Theory of the Practice of Curating New Media Art.” In: Beyond the Box: Diverging Curatorial Practice, edited by Melanie Townshead. Banff: Banff Centre Press 2003, 169-182.

Cook, Sarah and Barkley Aneta Krzemień. “The Digital Arts in and Out of the Institution – Where to Now?” In: A Companion to Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell 2016, 494–515. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.gla.ac.uk/10.1002/9781118475249.fmatter

Diamond, Sarah. “Silicon to Carbon”. In: Beyond the Box: Diverging Curatorial Practice, edited by Melanie Townshead. Banff: Banff Centre Press 2003, 141–168.

Ekeberg, Jonas. New Institutionalism. Oslo: Office for Contemporary Art 2003.

Gere, Charlie. “New Media Art in the Gallery”. In: New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul. Berkeley: University of California Press 2008, 13–25.

Giannachi, Gabriella. “The use of documentation for the preservation and exhibition: The cases of SFMOMA, Tate, Guggenheim, MOMA, and LIMA.” In: Documentation as Art: Expanded Digital Practices, edited by Annet Dekker and Gabriella Giannachi. London: Routledge 2022, 133–144. DOI: 10.4324/9781003130963-15.

Graham, Beryl and Sarah Cook. Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media. Leonardo Books. [2010] Cambridge: MIT Press 2015.

Groys, Boris. On the New. [Carl Hanser Verlag: 1992] London: Verso 2014.

Krajewski, Piotr. “An Inventory of Media Art Festivals.” In: Curating Immateriality: The Work of the Curator in the Age of Network Systems, edited by Joasia Krysa. DATA Browser 03. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Autonomedia 2006: 223–235.

Krysa, Joasia. Curating Immateriality: The Work of the Curator in the Age of Network Systems, edited by Joasia Krysa. DATA Browser 03. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Autonomedia 2006.

Mitchell, William J., Alan S. Inouye and Marjory S. Blumenthal. Beyond Productivity: Information Technology, Innovation, and Creativity. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press 2003.

Möntmann, Nina. “The Rise and Fall of New Institutionalism: Perspectives on a Possible Future.” In: Art and Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique, edited by Gerald Raunig and Gene Ray. London: MayFlyBooks 2009: 155–159.

Paul, Christiane. Digital Art. [2003] London: Thames and Hudson 2015.

Paul, Christiane. “New Media Art and Institutional Critique: Networks vs. Institutions.” In: Institutional Critique and after: SoCCAS Symposium Vol. II, 2006. http://intelligentagent.com/writing_samples/CP_New_Media_Art_IC.pdf.

Rossiter, Ned. Organized Networks: Media Theory, Creative Labour, New Institutions. Rotterdam: NAi 2006.

Quaranta, Domenico. Beyond New Media Art. Brescia: LINK Editions 2013.